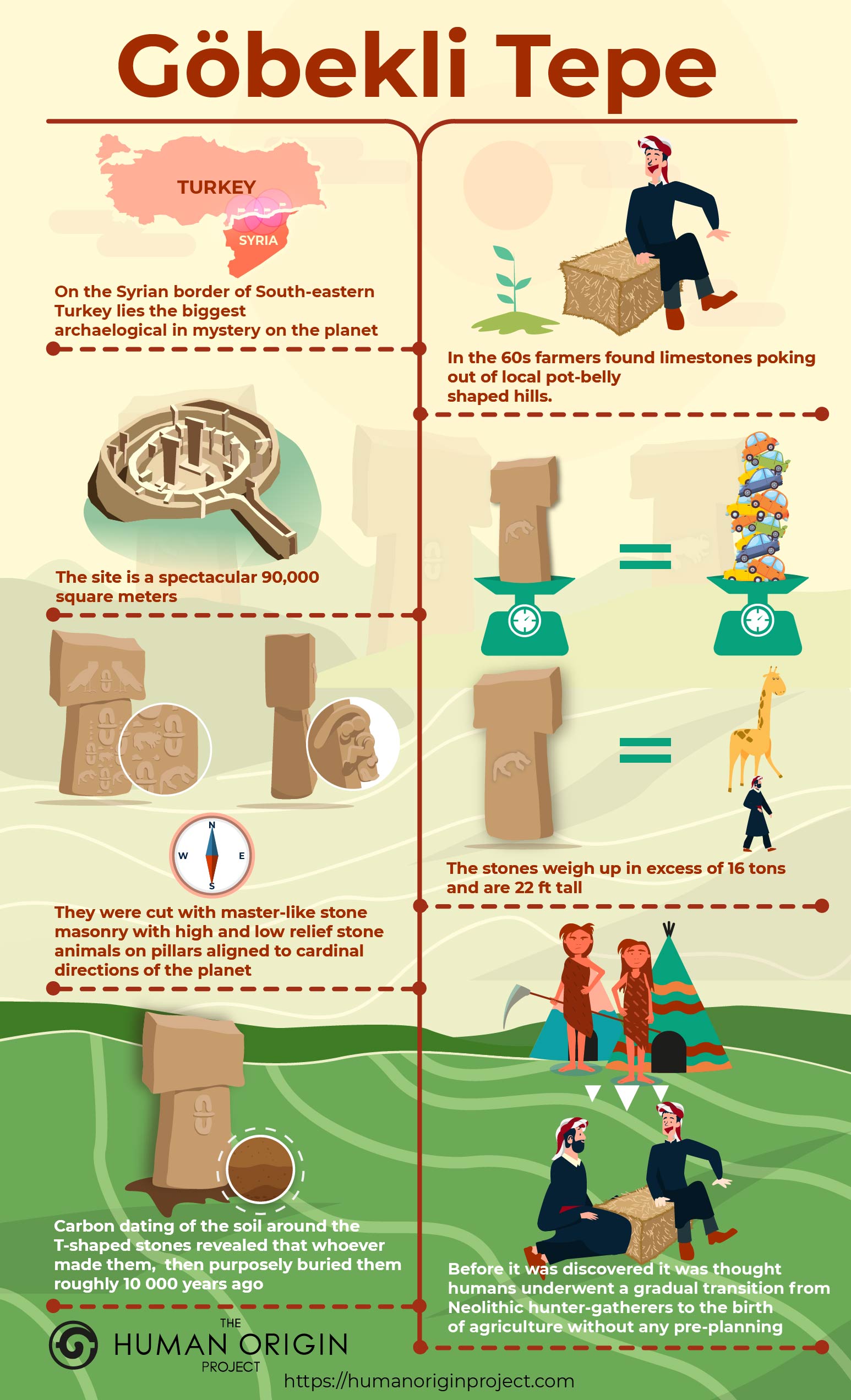

Based on everything we know, Göbekli Tepe shouldn’t exist. Located over 20 years ago on the Syrian border of Turkey it’s mystery remains unsolved. Why on earth was Göbekli Tepe built? It sits smack in the middle of the fertile crescent, where earliest humans began the agricultural revolution. Here lies ground zero for modern civilization, or as some have dubbed it, The Garden of Eden. In 2018, it was added onto UNESCO’s World Heritage List. For many reasons, it remains as one of the most baffling archeological sites on the planet. Is Göbekli Tepe the Oldest Temple in the World? Or is it much, much more.

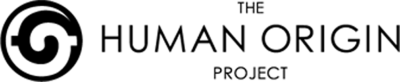

An artist rendition of the stone circles of Göbekli Tepe. Source National Geographic.

Göbekli Tepe is the oldest megalithic structure ever found on earth. Discovered in modern-day Turkey, and still yet to be fully excavated, it dates to a baffling 12,000 years old.

It’s not just the oldest site; it’s also the largest. Situated on a flat, barren plateau, the site is a spectacular 90,000 square meters. That’s bigger than 12 football fields. It’s 50 times larger than Stonehenge, and in the same breath, 6000 years older. The mysterious people who built Göbekli Tepe not only went to extraordinary lengths they did it with laser-like skill. Then, they purposely buried it and left.

These peculiar facts have baffled archeologists who have spent 20 years unearthing its secrets.

When was Gobekli Tepe Found?

The site is located close to the Syrian border, in the Southeastern Anatolia Region of Turkey, about 12 km (7 mi) northeast of the city of Şanlıurfa. Göbekli Tepe means in English, Pot-Belly Hill.

The first whispers of Göbekli Tepe came when local farmers found limestone poking out of the ground. In 1963, archeologist Peter Benedict conducted the first survey of the site. He described a “complex of round-topped knolls of red earth.”

Benedict was correct, but only in the most superficial way. He could have never have realized just how much he had understated what Göbekli Tepe really was.

Those pot-belly hills were the deepest and most ancient echoes of the human origin story. At the time, no ancient site suggested that Neolithic man could produce giant stone monuments.

The pillars remained sleeping under the earth until the arrival of someone who could recognize them. In 1994, German Archeologist, Klaus Schmidt, visited the site.

He instantly recognized that Benedict’s report had been wrong. The “knolls” he saw, were human-made mounds, and the flint shards crunching underfoot had been shaped by Neolithic hands.

Smith was familiar with Turkish Archeology, working nearby at Nevalı Çori. After it was flooded by Atatürk Dam, becoming part of the floor of Lake Atatürk, Schmidt was looking for a new Stone Age site. He was immediately drawn to Göbekli Tepe by the similar T-shaped pillars as Nevalı Çori.

Schmidt knew he had a big decision to make.

He would spend the rest of his life studying Göbekli Tepe.

What is Göbekli Tepe?

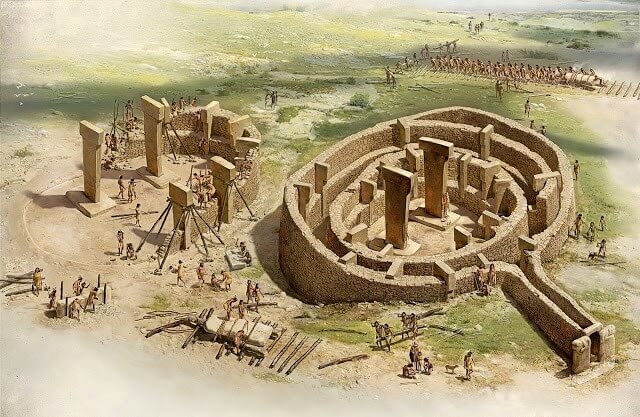

The excavated stone circles and T-shaped pillars of Göbekli Tepe. Source

Klaus Schmidt began the investigation of Göbekli Tepe with Heidelberg University in 1994. He would spend the next 20 years there until his sudden and unexpected death in 2014.

Schmidt and his Turkish wife bought a house in the nearby city of Urfa. He and his team would spend a morning at the site, returning for a late lunch and an afternoon processing the days finds.

Today, the site is opened under a modern shaded roof where visitors can walk the site.

The archeological findings that have unfolded over two decades are nothing short of astounding.

Göbekli Tepe is made up of a collection of stone circles containing ‘T’ shaped pillars. The circles were placed on flat bedrock some weighing in excess of 16 tons.

The site is so big, more than 90% of it remains underground. Currently, the exposed part is about the same size as Stonehenge. The rest of the staggering arrangement of stone circles were found with ground penetrating radar.

The T-shaped standing stones were placed in the center of each stone enclosure. It’s thought they depict people, perhaps those that directed the building of the site. The largest of the stones are up to 17 feet high. That’s the size of a very tall giraffe.

The T-Shaped Pillars of Göbekli Tepe in a Turkish Museum. Source

It’s unknown how the builders were able to shape, move and place stones of this size.

Half-a-mile across a limestone plateau from the main mound is a 22ft-long T-shaped monolith. It was never finished or moved to the main temple site.

Beyond the sheer scale, the site is geographically aligned to the north-south poles. Other researchers are revealing possible astronomical alignments and purposes. One including, as an observatory for Sirius.

The precision, mystery, and beauty of Göbekli Tepe boggle the mind.

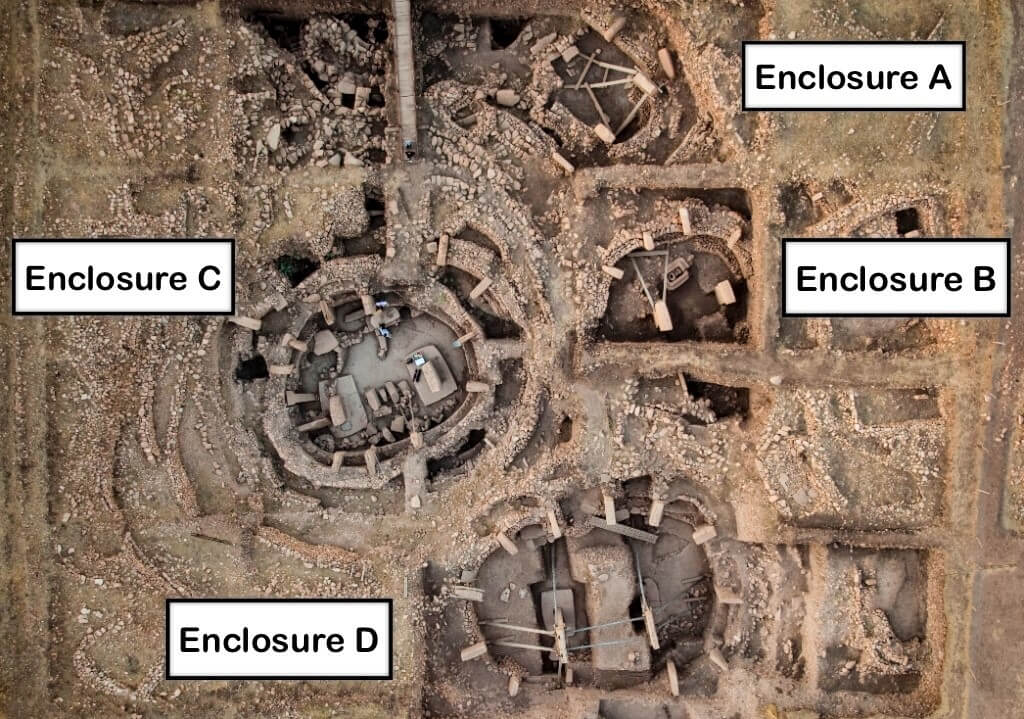

The enclosures of Göbekli Tepe show ancient astronomy and north-south pole alignment.

The world’s oldest artwork and stone carvings

Walking through the enclosures of Göbekli Tepe reveals depictions of animals, symbols, and human-like figures.

There are both high relief and low relief carvings found throughout the site. The precision and skill associated with these carvings are nothing short of remarkable.

A high relief carving means that the stone is cut on the outside of the larger piece. It is a complicated and advanced technique in stone masonry even by modern standards.

Precision high relief stone masonry of Gobekli Tepe.

The many animals depicted include foxes, birds, lions, scorpions, snakes, and boars. There is a scorpion the size of a small suitcase, and a jackal-like creature with an exposed rib cage.

The exact meanings of the carvings appear to be unknown. On one pillar a row of lumpy, eyeless “ducks” float above a boar, with an erect penis.

Another relief consists of the simple contour of a fox also with a distinct penis. Most mammals represented at Göbekli Tepe are visibly male, except for one fox, which, in place of a penis, has several snakes coming out of its abdomen.

Perhaps the most debated composition portrays a vulture carrying a round object on one wing; below its feet, a headless male torso displays yet another erect penis.

What happened at Göbekli Tepe?

In trying to find the age of Göbekli Tepe, carbon dating revealed a strange trend.

Whoever made Göbekli Tepe wanted to preserve its memory. To Schmidt’s astonishment, analyses of the soil around Göbekli Tepe revealed that it was purposely buried.

The materials used to fill the site were unusually uniform and dated to the same period. If this occurred naturally, there would be a spread of dates found in the material of the soil. The entire complex is also built on a hilltop, which usually means that soil should erode and not be deposited.

This site was active for about 1000 to 1500 years until the entire complex was buried around 10 000 years ago.

During their centuries of use, the circles and pillars were built and filled with debris. New pillars were started on top of or alongside the old ones. The circles thus stand at different depths and layers in the hill. Today, they have been connected by various wooden scaffolds, ladders, and walkways.

How old is Göbekli Tepe?

It is now understood that Göbekli Tepe was built in various stages. After one stone circle complex was completed, it was covered up, and a new one built. This mysterious feature of the site is entirely without explanation.

Radiocarbon dating of Göbekli Tepe has revealed the different ages of the stages and layers.

Enclosure C – 7560-7370 BC

Enclosure B – 8280-9270 BC

Layer III – 9110-8620 BC

Layer III – 9130-8800 BC

What makes it all the more difficult the grasp is that the stages appear to get worse and worse. The earliest enclosures are the largest and most sophisticated. Not only artistically but also technically. These progressively drop as the site gets younger and younger. The construction skill appears to be decreasing.

These features of Göbekli Tepe are challenging everything thought of the Neolithic revolution. It’s logical to assume the more you do something, the better you should get.

Whatever the reason, the sheer size of the site means that burying it would have been an incredible task. To cover it completely would have taken a vast number of people countless hours and effort.

It must have been for a good reason.

What was Göbekli Tepe used for?

Explanations of Göbekli Tepe range far and wide. What makes this site so important is that it appears in the area of the world that the first signs of civilization and culture arise.

It coincides perfectly with the agricultural revolution. These were the first people to plant and farm crops. All strains of domesticated wheat found around the world can be traced to the areas surrounding Göbekli Tepe.

There are also the first signs of animal husbandry, agriculture, and metallurgy in the nearby landscapes. However, to this day, no signs of habitation found near the site. This may suggest that Göbekli Tepe could have been a place of worship, innovation or teaching, rather than a livable area.

When considering possibilities, the context must be analyzed. Göbekli Tepe was built around 8000 years before The Great Pyramid of Giza. That’s a double the span of time from the pyramid builders to present day.

These large periods of time leave very few traces of human society. It creates a big problem in trying to understand what Göbekli Tepe was.

In Schmidt’s words, the fragile nature of what is left for future generations find is very limited.

“Even one thousand years later, nothing is left of this world,” he said. “Why should there be anything left six thousand years later?”

In short, we don’t know exactly what Göbekli Tepe was used for. However, with more than 90% underground, it makes sense that we should be making every effort to learn whatever this purpose was.

Who built Göbekli Tepe?

Theories of the Neolithic revolution describe the transition from hunting-and-gathering to farming and on to modern civilization. It was thought for two hundred thousand years before Göbekli Tepe, before the last ice age—people lived as hunter-gatherers before rising into civilized society.

The consensus has long been that hunter-gatherer societies could not build such large monuments. The reason is they don’t generate a surplus of food and are generally in smaller numbers than would have been required to complete the site.

Generally, theories suggest a gradual build of culture, populations, and the need for agriculture.

Göbekli Tepe breaks that model.

Building Göbekli Tepe would also have required some division of labor among planners, technicians, and workers. Did these social developments pre-date, rather than result from, the shift to agriculture?

The workers needed a stable food supply, and the area was rich in wild species like aurochs. There was a steady supply of einkorn, one of the ancestors of domesticated wheat. One theory suggests that agriculture grew out of a need to build Göbekli Tepe.

In his books, Schmidt discusses a revamped Neolithic revolution model where the need to build then created the need for agriculture.

The people of Göbekli Tepe weren’t wiped out, like other lost civilizations. They simply packed up and went somewhere else—became someone else. Perhaps they are still around us today, or are us?

The problem remains that it appears out of nowhere. No other ancient megalithic sites are found for thousands of years after. No ancient society with these capabilities is remotely near this point in the historical record.

Challenges and mysteries that the people of Göbekli Tepe left us are many. They preserved enough for us to change our idea of who they were. But not yet enough to exactly pinpoint those exact origins.

Conclusion:

Göbekli Tepe should leave you feeling uncomfortable. There are so many unknowns. At the same time, there is so much evidence and story remaining under the fertile soils of Turkey.

The more that is discovered about the site, the more questions are raised. How it was made? Who made it? What was its purpose and why on earth was it buried?

Our current answer is that we simply don’t know.

The messages stored at Göbekli Tepe laid dormant for nearly 10 000 years. Whoever built it was successful in saving whatever it was they were trying to preserve.

Now it’s up to us to decipher it.

What do you find most puzzling about Göbekli Tepe?

Join the conversation in the comment section below.

Göbekli Tepe is the oldest, biggest, and most mysterious archaeological site on the planet.

Göbekli Tepe is the oldest, biggest, and most mysterious archaeological site on the planet.