Today the best known version of cosmology is the Big Bang Theory. It’s the idea that all matter that we see today came from one single event that expanded and created the universe.

In ancient China religion and cosmology were not separated. There existed a description of the creation of the universe that appeared right at the start of their culture. This cosmology is still alive today, and is conveyed through Buddhist practices and teachings, yet its origins go back further than the written word, beginning with an oral tradition at least 5,000 years old.

Where did this knowledge come from? And how can we interpret it today?

Chinese religion and cosmology holds its roots in such high regard that much of their culture revolved around it. This was expressed through in-depth symbolism and impressive mnemonic devices that continually reminded individuals of their place on the earth.

Ancient practices also linked these ideas to how the universe forms.

The principles of ancient Chinese cosmology can be interpreted today. They provide some of the finest examples of preserved ancient knowledge.

A look at some aspects of this cosmology reveals an ancient civilization that has successfully transmitted their most sacred knowledge through the ages. Conceptual notions as well as physical structures have enabled the earliest of their teachings to remain alive and accessible to us today.

The Ancient Chinese Religion

In early Chinese religion and cosmology, multiplicity–or the creation of the universe–is thought to have arisen from unity. It was believed that in order for space to come into existence, unity must disperse into multiplicity, or duality. This idea runs parallel to the big bang in western science.

However, the ancient Chinese civilization described it as order coming from chaos, a central theme to their teachings. This chaos was thought of as watery and non-material, similar to the primordial waters discussed in the biblical book of Genesis.

One of the fundamental aspects of Chinese cosmology was the idea of squaring the circle, which was expressed in countless ways through the Chinese civilization’s scientific belief systems as well as their religion.

What is Squaring the Circle?

This is the ancient notion of reconciling the heavens and the earth. Symbolically, a square is representative of the earth and all things material, as well as conscious thought; it has edges and corners, meaning that it is physical and can be measured. The circle, on the other hand, is a metaphor for the heavens, as well as the non-material and subconscious, because it is perfectly round it has no beginning or end.

Another way of expressing this is through the hermetic saying, ‘As above, so below’, the idea that the macrocosm of the Universe is unfolding within each individual on a microcosmic level. It was believed that if individuals understood their place within the greater processes of creation, and they went with themselves to explore this creation, they would ultimately live more wholesome and meaningful lives.

The metaphor of squaring the circle was not only employed in China, but also throughout much of the ancient world including Egypt, South America, as well as Greece and the UK.

There are examples found all over the planet of cultures trying to convey their attempts of squaring the circle. One of the clearest examples of this is through the grand symbol of Freemasonry, which makes up their symbol of a setsquare and a compass. The setsquare measures the squareness of the earth, while the compass is used to measure the roundness of the heavens. The idea is to try and understand the two in order to gain insight into the secrets of the universe.

The Chinese Magic Square & Squaring the Circle

One of the earliest examples of magic square imagery is found within ancient Chinese depictions of their creator gods, Fu-xi and Nu-wa. Fu-xi is depicted holding a set square, and Nu-wa a compass. The pair are often shown together, holding their respective tools for measurement.

The magic square was extremely symbolic and important to the Chinese religion. The square is thought to balance yin and yang as well as the concepts of Qi and Feng Shui, and acts as a tool for divinatory purposes.

The magic square was not just symbolic, it had physical aspects too. The well-field system of land distribution in ancient China was a physical manifestation of the 3×3 magic square. The layout of China’s earliest cities was also in accordance to the magic square, adding a physical dimension of depth to the already complex symbolism and function.

Along with these ideas, the magic square embodied aspects of astrology and astronomy. By understanding the numbers on a personal level, individuals could determine when to perform specific tasks, as well as where to build houses, bury their loved ones, or plant specific crops.

How Does the Magic Square Work?

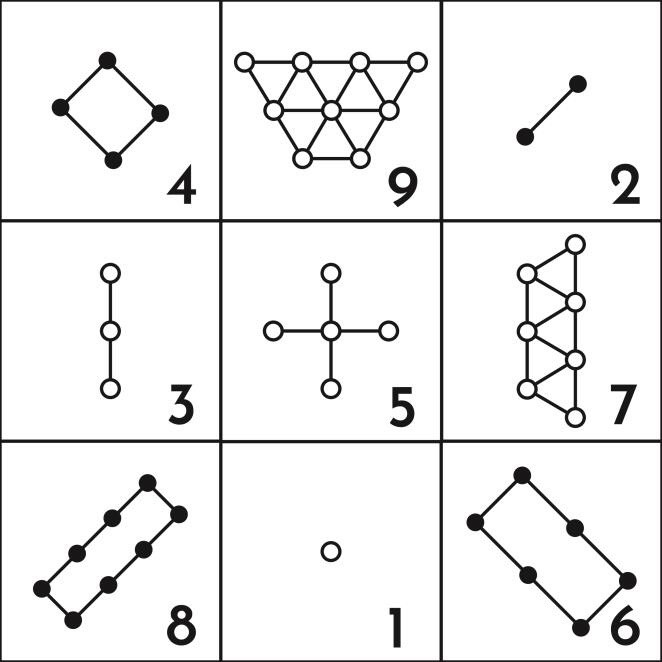

The numbers 1 to 9 make up the magic square, with the number 5 always located in the middle of the grid. The numbers are arranged in such a way that the sum of each row is equal to the sum of each column, as well as diagonal rows. In the earliest magic square, a 3×3 grid, the sum of these numbers all add up to 15.

Odd numbers are considered to possess Yin, or feminine energy, while even numbers are thought of as Yang, or masculine. Each number has different properties and different configurations of these numbers result in different outcomes and interpretations depending on the magic squares used. The magic square also served as the basis for the trigrams of the Yi Jing, or I Ching (the Book of Changes), a Chinese divinatory tool and one of the world’s oldest books that is still widely used today throughout China and the rest of the planet.

Origins of the Magic Square – The Story of Lo Shu

The dating of the myths vary according to historians, but it is generally agreed that sometime around 3000 BC marks the first appearance of the magic square.

The myth begins with an ancient turtle called Lo Shu, who is said to have emerged from the Luo River after a great flood. As Lo Shu emerged from the newly calmed waters, Fu-xi, the mythical founder of Chinese civilization, observed a 3×3 grid on the turtle’s back, with dots that added up to different numbers. From the marking’s on Lo Shu’s shell, Chinese civilization was given the concept of the magic square, (depicted below.)

The way the numbers are arranged in the square can vary; the above image can be mirrored or rotated as long as the numbers still equate to 15.

Not only did the magic square prove to be extremely important within the ancient Chinese civilization, the turtle also became one of the most important symbols and pivotal aspects of the civilization’s cosmology.

Symbolism of the Turtle

There are many layers and meanings associated with the symbolism of the turtle. Many of them rest on the cosmological concept of squaring the circle, which was not only held in absolute reverence by ancient Chinese civilization, but also by many other ancient cultures around the planet.

What is the Symbolic Meaning of the Turtle?

To help members of the ancient Chinese civilization remember their cosmology, many different mnemonic devices were developed, usually in the form of animals, as their physical characteristics were easy to remember and so too were the cosmological traits they symbolized.

The turtle was possibly the most important symbolic animal for the ancient Chinese civilization, which is one of the oldest Chinese symbols, with origins deep in prehistory. It is often associated with creation stories.

In early Chinese mythology, the mother goddess Nu-wa is said to have cut off the legs of a turtle to use as pillars to hold up the crumbling sky, reinforcing the idea that the turtle represents the cosmos. The curve of its shell represents a hemisphere of sky while the flatness of its body represents the earth, and signifies the squaring of the circle, the union of heaven and earth. The turtle’s shell and body were also considered by other ancient cultures – such as the Dogon of West Africa – to symbolize the joining of the sky and earth.

It is specifically stated that these mythological pillars are not cardinal markers. Instead, they are thought to represent the spaces between the four cardinal points, with the head and tail acting like the hands of a compass. Another symbolic reference within this story is the separation of the sky and the earth, ultimately thanks to the pillars that the turtle provides.

Not only was the turtle’s shell the basis for Chinese civilisation’s magic square and city layout, it also embodied extremely complex symbolism that branched off into other aspects of their culture. This has led some researchers to attribute the turtle shell as the source of Chinese mandalas as well as the object which the zodiac rests upon, (a theme similar to the World Turtle of Indian Vedic cosmology who carries four elephants harnessing the planet.)

What is the importance of a Buddhist Stupa?

Chinese religion, particularly Buddhism had practical ways of conveying their same ideas.

This is most apparent in the layout of their ritual shrine known as a Buddhist stupa. The original stupa was a personal ritual shrine built with a square base and a rounded top, yet another way the Chinese civilization expressed the concept of squaring the circle.

The circular shape of the stupa represented multiplicity, and the construction of the shrine itself signified the idea of order manifested through chaos. The construction and layout of the stupa continually reminded the individual of their place within the creation of all things–something that was conceptually acted out both by building and using stupas.

Conclusion

The ancient Chinese religion and cosmology is full of complex and multi-layered meaning. There are many other aspects to the system that are as important and influential which we will explore in future.

Although much of the Chinese civilization has been documented and discussed by researchers, the origins and meaning of much of the earliest tales have never been agreed upon.

We are only just beginning to put the pieces together to understand this advanced cosmology.

What do you think the source and inspiration for this set of teachings was?

Further Reading

China’s Cosmological Prehistory by Laird Scranton

Symbolism of the Stupa by Adrian Snodgrass